Putting Third Places First

Beal St. George

Each of us, like it or not, is tasked with the ongoing life practice of accepting unpredictability. Sometimes that ends up being a good thing: serendipity, unencumbered, can delight. So although I hadn’t planned to wind up studying bowling alleys in college, it turns out that their existence has brought a lot of meaning to my life.

It was while reading Robert Putnam’s Bowling Alone—a cautionary exploration of the decline of social capital—that I first intellectually grasped the concept of the third place, though I’d been readily availing myself of third places since, well, forever: after school, spending hours at the library reading (gasp!) actual books; in the outfield for the local softball team; in cafés, listening to my surroundings.

Putnam (who, coincidentally, was born in Rochester, NY!) is the celebrated grandfather type of all liberal arts college political science departments. In Bowling Alone, he investigates the causes behind the decline in membership of social spaces (from bowling leagues to churches), and in our mind’s eye, we are left with the bleak image of the lanes: run-down, low-slung, nearly deserted at eleven P.M., just a few stragglers belly-up to the bar in low spirits and the increasingly rare crack! as bowling ball meets pins.

The third place, for those unfamiliar, is exactly what it sounds like: a place, where people gather, that isn’t home (the “first” place) or work (the “second”). Coining the term in his 1989 book The Great Good Place, sociologist Ray Oldenburg posits that third places are important for everything from civil society and engagement to the institution of democracy, to establishing your own sense of place in the world.

Oldenburg distinguishes a third place as a place that grounds community life; think libraries, gyms, parks, cafés, places of worship, and, of course, bowling alleys. Though never actually referring to bowling alleys as third places, Putnam’s writing draws on the same thread: his point, broadly, is that community engagement has declined since the 1960s and that this decline has had—and continues to portend—calamitous results.

Academics have since elucidated eight characteristics of third places (perhaps because sociologists constantly feel the need [read: threat] to measure and quantify their extremely squishy social science), the specifics of which I won’t go into now, but which, broadly, are useful in distinguishing the term. Third spaces are neutral spaces, creative and generative spaces, spaces of familiarity and also of new encounters. They’re accessible and accommodating (read this as: of newcomers and regulars; of people of all abilities, backgrounds, identities; and also as a descriptor of the general vibe). Third places are not snobby. They’re wholesome.

Increasingly threatened by both careless digitization and maximal individualism, third places play a vital role in our collective society and our individual psyches—which is why it’s crucial that they be preserved.

For my part, I’ve mapped my life, in narrative terms, much more by my first and second places than by my third places. But when given a moment to think about it, one can clearly see that it is the places we go in the interstices—the corner store you dash into for tortillas on your way home from work, the beloved hairstylist’s chair you always leave feeling more yourself, the community garden where you stop to say hi to neighbors—that create texture in the fabric of our lives.

A vital tenet of the third place is its intentionality: the furniture chosen to make people feel comfortable, to make it easy to talk to your neighbor; the music you play (or don’t play); the agreement that, in libraries, we speak in hushed tones, and only when absolutely necessary. Each third place is crafted (a term I use loosely, since I think this intentionality only takes us so far—and of course it is the community, that which blossoms from the environment, that is really adding value to our lives) to nurture the kind of belonging it hopes to create.

We must be careful, then, when it comes to creating online “places,” that they truly are net-additive, not net-destructive (and I don’t mean that kind of ‘net!). No matter how much fun you’ve had on TikTok or how many vintage finds you’ve bought off neighbors on Facebook Marketplace, you likely wouldn’t say it’s a stretch to call the Internet the Wild West of our time: inequitable, terrifying, dangerous, full of racist colonizers.

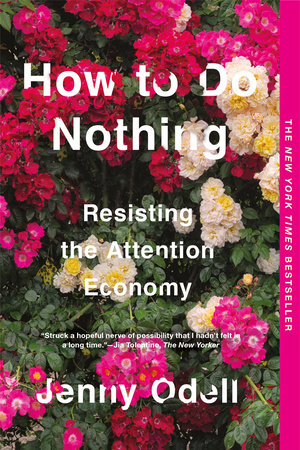

One can make the case for a virtual third place: that is, after all, the world we are now living in. But if one benefit of third places is their “placefulness,” which, in her book How To Do Nothing, Jenny Odell defines as “living with grounded consciousness in the present time and location,” then let’s be mindful about casting all digital spaces as third places. There are communities to be found online: of other queer youth like you, of people who play the same video games you do. These could be the intentional kind of digital third place that Oldenburg, now 90, didn’t originally conceive of, but might welcome.

What is not an online third place? Social media. Sites where sharing your own experiences neither furthers someone else’s nor invites thoughtful conversation—sites that instead create an (Odell, again) “algorithmic ‘honing-in’ [that] would seem to incrementally entomb me as an ever-more stable image of what I like and why.”

And here’s where we get to the maximal individualism. We’re told, on those sites, to “be ourselves.” But what, asks Odell, is a personal brand, “other than a reliable, unchanging pattern of snap judgments: ‘I like this,’ and ‘I don’t like this,’ with little room for ambiguity and contradiction”?

Third places are magical precisely because of their ability to conglomerate a bunch of different people in one place—and their invitation to talk about something (anything!). They are the anti-algorithm. We need more of them.

I’ve also observed that third places are increasingly capitalist: places like the grocery store (which used to be the corner store or the general store—a “town center” that fostered commerce and community) are now solely places where we go to spend money. We’re whisked in and out—cart-aisles-checkout-parking-lot—as much by our own desire to maximize productivity as by the store that wants us to spend-spend-spend.

Golf courses, neighborhood bars, paint-and-sip classes, all of which could be called “third places” aren’t so much in that they are economically curated: you’ve got to pay to play. What I’m referring to is built upon more serendipity, more diversity of experience, and a bit more—at least in our commodified world—subversiveness.

And we, o careless humans, have also turned many third places (cafés, the pizza shop where we’re all standing waiting for food, the grocery aisle with seventeen different kinds of canned beans) into phone-scroll emporiums: we’re glued to our devices, heads down, individualists that we are, unwilling to look around us and meet someone else’s eyes. Which of these cans of beans is best for my recipe? You ask the Internet instead of the woman next to you picking out her own beans, who is herself much older than the Internet, and who probably knows.

I believe placefulness is a practice. It involves taking in our surroundings, even when they aren’t easily described as “here” or “there,” and talking to the people in those places—this is largely what builds our community. It’s uncomfortable; we’re accustomed to assuming the cocktail shrimp position: hunched over our phones, bottom-feeders in an ocean of algorithmic swill.

Which brings us all the way back to the beginning, to the unpredictability. Let’s have more of it. I’m not saying we constantly need to be talking to strangers, but the simple recognition that we, humans, are here in community with other humans, is an ancient practice (and, today, a perspective shift) that Big Phone and Big Algorithm and Big Capitalism want us to leave behind entirely.

So what happens when you step outside in the morning, wave to your neighbor, then actually stop to talk to them, despite feeling momentarily awkward, and end up smiling to yourself as you duck into your car to go to work? Or when you leave your phone in your bag while you wait for your sandwich order, meet someone else’s eyes, and ask, what’s your favorite thing on the menu? I implore you to find out.