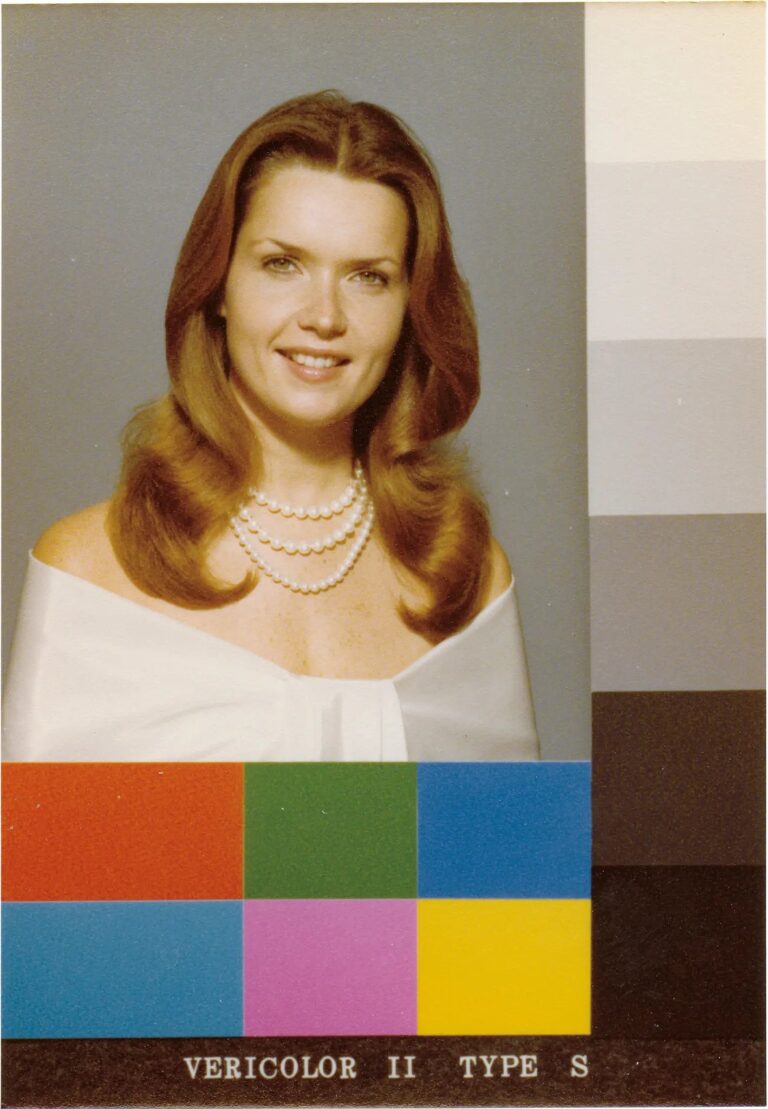

It began one warm sunny day in Hollywood in the 1980s, a photographer welcomes a stunning African-American model into the bright, airy studio. As palm trees sway back and forth in the window, the camera continues to wind and snap until the Kodak roll reaches its end. At the local print shop, the roll is tossed in a metal tin and developed with a perfect mixture of chemistry. The film drips dry on the rack, and the photographer eagerly awaits the perfectly calibrated prints. Once finished, the photographer races down Hollywood Boulevard to see their creation. They ripped open the package, only to find the model was barely visible.

Who is Shirley?

The Hollywood printing shop likely calibrated the image using a Shirley Card. Created by Kodak and named after an employee, these cards were printed and distributed to printing shops to calibrate skin tones, shadows, and light for perfect photographic prints. However, every Shirley model was white. It wasn’t until the 1970s when a Kodak photographer, Jim Lyon, began to fix the issues of accurate skin tone representation (del Barco, 2014).

Even as Kodak attempted to fix the Shirley Card, the biases towards whiteness in film, media, and technology were more than just skin tones; it was everything that encompassed the appearance, standards, and culture of whiteness (Lewis, 2019).

Technological Advances Include Racial Biases

Racism in technology is a proven issue that still affects our society today. (If you haven’t, you should read our other article, “4 Examples of Racism in Technology and What We Can Do About It”). Algorithms, facial recognition, and market research have been biased toward whiteness, offering countless examples of racial discrimination and stereotypical targeting.

So... is AI Racist?

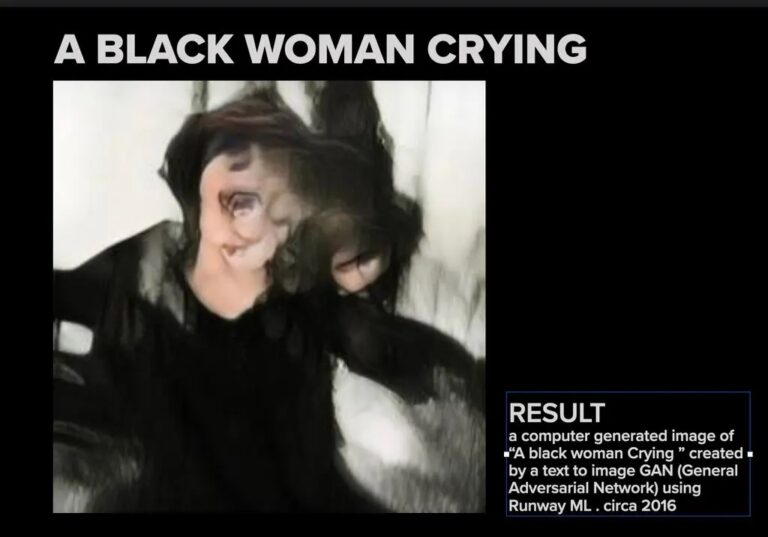

AI’s popularity and everyday usage, thanks to ChatGPT, increases the fear of AI completely taking over our jobs, but the conservation seems to ignore one of AI’s more looming scares… is it racist? Long story short… yeah, it’s racist.

But Whyyyyy is AI Racist?

Let’s take a deep dive. Tina Cheuk, assistant professor at California Polytechnic State University, wrote the insightful article, “Can AI be racist? Color-evasiveness in the application of machine learning to science assessments,” which deconstructs what whiteness AI favors. Research from Annamamma et al. in 2017 revealed that “…algorithmic models employed in science assessments in the United States reveals that their supposedly objective “color-evasive” nature, in fact, embraces analyses and answers that affirm “whiteness”– the notion that the culture, language, and representations of White people are the standard against which all answers out to be seen, heard, and measured,” (Cheuk, 2021, p. 826).

Similar to the Shirley Cards from 60+ years ago, AI algorithms do not simply favor whiteness but embrace many biases of whiteness as well (Cheuk, 2021).

Unfortunately, biases run deep, and the West’s systematic racism has continued to spread and infect newer technology areas. James E. Dobson, author, and cultural historian at Dartmouth College, states, “It’s hard to separate today’s algorithms from that history because engineers are building on those prior versions”(Small, 2023, pp. Section C, Page 1).

Systemic Racism in AI and Its Effects

AI further entrenches us into the same harmful biases and stereotypes that existed far before technology. AI’s racial harm, unfortunately, goes far beyond name-calling. AI continues to perpetuate housing, tenant, hiring, and financial discrimination, further fueling the systemic racism issue we already have (Akselrod, 2021).

The representation of BIPOC people in AI has continued to cement some of the worst stereotypes of the West’s worldview. Why have the developers, engineers, and tech giants allowed this to happen? Well, the answer requires an even deeper dive back to the root of technology’s origins, not too far off from Kodak’s white Shirley Cards calibrating every skin tone. In technology experimentations, “There was very little discussion about race during the early days of machine learning, according to his research, and most scientists working on the technology were white men” (Small, 2023, pp. Section C, Page 1). Throughout American history, the possibility of people of color entering these high-level workforces has been difficult. The culprit, which also enables AI’s racist tendencies, is systemic racism.

As defined by the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, systemic racism is “…an infrastructure of rulings, ordinances, or statutes promulgated by a sovereign government or authoritative entity. In contrast, such ordinances and statutes entitle one ethnic group in a society to certain rights and privileges while denying other groups in that society these same rights and privileges because of long-established cultural prejudices, religious prejudices, fears, myths, and Xenophobia’s held by the entitled group” (OHCHR, 2022).

Wow, that’s a lot of words. Luckily, the United Nations provided examples to help understand the definition. An example of systematic racism in the United States would be, “Colored people are not allowed to live in this neighborhood” (OHCHR, 2022), which applies to both Jim Crow and redlining history in America. Ultimately, the government’s lack of drive to help combat discrimination against people of color has continued to manifest little accessibility and fewer educational and employment opportunities. The government’s inaction has left minority groups little to no chance to step in the same room as those white men experimenting with machine learning in the 1970s. This discrimination may explain why AI has these preconceived and stereotypical notions.

America’s history of segregation and discrimination has now carried over into the future of technology, broadcasting harmful stereotypes. Clearly, AI has a lot of learning to do, but some are not giving up hope (Small, 2023, pp. Section C, Page 1).

According to the New York Times, “the curator added that her own initial paranoia about A.I. programs replacing human creativity was greatly reduced when she realized these algorithms knew virtually nothing about Black culture” (Dinkins, 2023, pp. Section C, Page 1).

However, Stephanie Dinkins, the inaugural recipient of the LG Guggenheim Award for technology, is a current artist based in Brooklyn who is not giving up on AI’s flaws and its erasure of history. (Dinkins, 2023, pp. Section C, Page 1).

What Can We Do?

Making positive change can be daunting, especially when big tech companies, backed by millions, if not billions of dollars are the ones to blame. The American Civil Liberties Union, or ACLU, has initiated a Call to Action on the Biden administration to fix the racial injustices ingrained in AI in 2021. In August 2023, the White House published a release titled, “Biden-Harris Administration Launches Artificial Intelligence Cyber Challenge to Protect America’s Critical Software,” summarizing the commitment to working with the world’s leading AI companies to make their software more secure (White et al. Room, 2023).

However, a quick Control + F search reveals that the statement covers nothing about race or racism. However, according to the announcement, this press release is “…part of a broader commitment by the Biden-Harris Administration to ensure that the power of AI is harnessed to address the nation’s great challenges and that AI is developed safely and responsibly to protect Americans from harm and discrimination” (White et al. Room, 2023). In the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy, they noted that “designers, developers, and deployers of automated systems should take proactive and continue measures to protect individuals and communities from algorithmic discrimination and to use design systems equitably” (White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, 2023). Time will tell how the federal government’s involvement or inaction will affect the future of AI.

Keep Advocating For Accurate Representation

It’s important to keep in mind that even though a lot of white people do not believe they are racist, institutional racism is still ever present in American society (OHCHR, 2022). White people must actively combat racism and advocate for change, or they continue to be a part of the problem. To help dissolve this issue, we must empower the community to take the necessary steps toward investing and advocating for anti-racist education.

People and programs learn racism similarly by passively consuming media saturated with white supremacy ideals. However, the solution starts with the people working behind the screens to unlearn their biases and solve the broader issue. Luckily, there are many opportunities for us to all actively unlearn these biases. The Chicago Public Library has a community-curated list of some of the most impactful anti-racist books listed here.

Luckily, the American Civil Liberties Union (also known as the ACLU) has already started urging the Biden-Harris administration to take action against AI’s harmful biases. In their article, “How Artificial Intelligence Can Deepen Racial and Economic Inequities,” they invite readers to join their volunteer team to call elected officials to help defend everyone’s civil liberties and address racism in technology. More information on participating is available here.

Education and willingness to learn, adapt, and take accountability are some of our best defenses against ingrained racism.

Sources

Akselrod, O. (2021, July 13). How Artificial Intelligence Can Deepen Racial and Economic Inequalities. ACLU. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.aclu.org/news/privacy-technology/how-artificial-intelligence-can-deepen-racial-and-economic-inequities

Algorithmic Discrimination Protections. The White House: Office of Science and Technology Policy. Retrieved September 25, 2023, from https://www.whitehouse.gov/ostp/ai-bill-of-rights/algorithmic-discrimination-protections-2/

Cheuk, T. (2021). Can AI be racist? Color-evasiveness in the application of machine learning to science assessments. Wiley, 105(5), 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21671

Del Barco, M. (2014, November 13). How Kodak’s Shirley Cards Set Photography’s Skin-Tone Standard. NPR. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.npr.org/2014/11/13/363517842/for-decades-kodak-s-shirley-cards-set-photography-s-skin-tone-standard

Lewis, S. (2019, April 25). The Racial Bias Built Into Photography. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/04/25/lens/sarah-lewis-racial-bias-photography.html

Saunders, J. D. (n.d.). 5 Reasons Representation in Media Matters. Black Illustrations. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.blackillustrations.com/blog/representation-matters-5-reasons-representation-in-media-matters

Small, Z. (2023, July 5). Black Artists Say A.I. Shows Bias, With Algorithms Erasing Their History. New York Times, CLXXII (59,840), Section C, Page 1. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/04/arts/design/black-artists-bias-ai.html

Systemic racism vs. institutional racism. (n.d.). Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved February 21, 2022, from https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Racism/smd.shahid.pdf

Wessling, M. (2023, April 7). The “Shirley Card” Legacy: Artists Correcting for Photography’s Racial Bias. National Gallery of Art. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://www.nga.gov/stories/the-shirley-card-legacy.html