Limbo: A Book List

Beal St. George

Liminal spaces are places of transition (you can read that literally, metaphorically, philosophically…) and they satisfyingly scratch an itch somewhere deep inside me. Liminal spaces are at once unsettled and unsettling, comforting and comfortable, transformative and deeply ordinary.

Many have written very eloquently about, or from within, these states of limbo, so I compiled an eclectic list of books I’ve read recently that each, in their own entirely unique way, attends to this concept.

Pick one up the next time you’re at the library, or from your local bookseller (here’s an up-to-date list of local bookstores thanks to Day Tripping Around Rochester).

“While punctuality lies at the heart of what we typically understand by a good trip, I have often longed for my plane to be delayed — so that I might be forced to spend a bit more time at the airport.” So begins this slim volume by de Botton, who spent (obviously) a week at London Heathrow Airport as “writer in residence.” The book is organized into four states of limbo: Approach, Departures, Airside, Arrivals. On every page, the text is punctuated by entirely ordinary, and therefore quietly poignant, photos.

From the “no man’s land of the aircraft” to the incongruous and all-consuming terminal shopping experience, liminal spaces abound, and de Botton’s gentle yet pointed commentary highlights both the great loneliness and the stirring attractiveness that lures us all to dream about and engage in the great miracle of flight.

This book is many other things besides liminal: it’s a protest novel commenting on the dangers of totalitarianism and the politics of collective and individual memory. It’s an exploration of magical realism. It’s re-readable (as in, every time you do, you might find something new). It’s on this list, however, because of its structure: written in seven distinct parts, two of which share the same name, this book could read more like a collection of stories, until you realize that each is also a political commentary, or a philosophical investigation, or an autobiographical recounting.

Additionally liminal: Kundera wrote the book in his native Czech, but was forbidden from publishing it in Czechoslovakia, which was at the time under Russian occupation; the book was instead first published in France in 1979, and in 1980, was translated to English and published in the US and Canada.

Cute, queer romance novel. ✅ Likable, flawed main character. ✅ Comfortable, speedy writing. ✅ BUT ALSO! A New York City subway meet-cute between August (our aforementioned main character) and Jane (badass queer punk rocker, several years older than August). It’s sweet, and coincidental, when they keep happening to be on the same train, no matter the time of day.

August finally works up the courage to ask Jane out, but Jane doesn’t show up for the date they’ve planned. The explanation for her absence is not a reason we might’ve expected (inability to commit, cheating on girlfriend, addicted to work)—no! THE REASON is purely liminal: Jane is literally suspended in time. Having gotten on the Q train in the 1970s, she’s been time-traveling since then, and is trapped for eternity, physically unable to get off. It’s a sweet book. You (obviously) must suspend your disbelief in order to really enjoy this sci-fi-lite queer romance novel, and I recommend you try.

I’ll admit up top: this book is headier than I wanted it to be. It has an index. It is extremely well-acclaimed, and Jenny Odell is really smart. It is doing a challenging thing by attempting to lay out a vision of something that currently doesn’t exist, a thing that is antithetical to our entire world: the idea of disengaging from the attention economy, that which occupies our entire lives—capturing, optimizing, algorithm-ing everything that we do—and instead choosing to engage in time, space, and “placefulness” (if the attention economy represents “placelessness”).

In her introduction, Odell asks, “what does it mean to construct digital worlds while the actual world is crumbling before our eyes?” If we’re always honing our selves into what is of course an impossible perfection, then ambiguity and contradiction cease to exist, capitalism wins, we don’t learn from our experiences, and we continue to harm our environment. This book invites many limbos, including the discomfort of not knowing and the intrigue of plurality, and through it, Odell offers a roadmap for reawakening to the world and its messiness, and for reorienting our attention for our collective benefit.

True: in February of 1862, during the first year of the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln lost his third son, Willie, then eleven, to a deadly fever. Reports from the time indicate that Lincoln, in his deep sadness, had repeatedly visited the crypt where his son was interred to hold the boy’s lifeless body in his arms.

George Saunders, from here, imagines, and in doing so, epitomizes liminality: Willie Lincoln is “in the bardo,” a transitional state after death and before rebirth, according to Tibetan tradition. Here is where the book takes place: between death and peace, in purgatory, amidst ghosts both hilarious and horrifying.

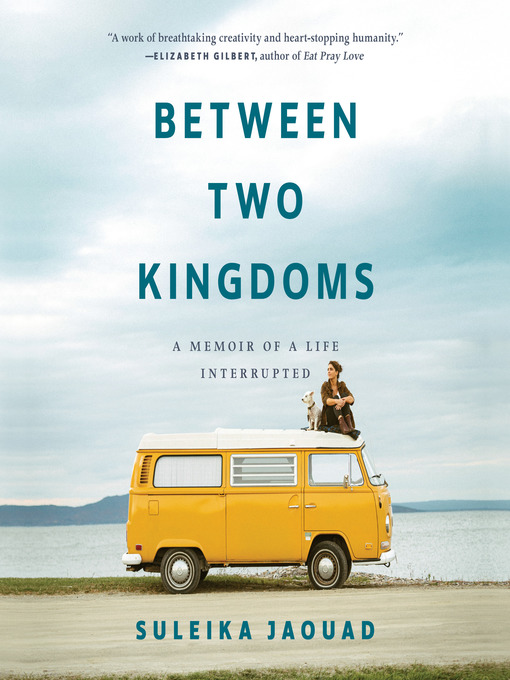

Jaouad has received much acclaim for this memoir chronicling her life in the wake of a leukemia diagnosis. In it, Jaouad recounts a four-year struggle against the odds of survival, and, after doctors declare her the victor of her battle, she sets off on a 100-day journey around the country. “I’ve spent the past fifteen hundred days working tirelessly toward a single goal—survival. And now that I’ve survived, I’m realizing I don’t know how to live.”

The book’s title is drawn from an essay by Susan Sontag, “Illness as Metaphor,” which appeared in a 1978 issue of the New York Review of Books, in which Sontag writes, “Everyone who is born holds dual citizenship, in the kingdom of the well and in the kingdom of the sick.” Between Two Kingdoms was released in 2021, and in November of that same year, ten years after her first bone marrow transplant, Jaouad learned that her illness was back. She’s still sharing her experiences, building creative community, and in every way she can, transforming isolation and interruption into connection and creativity. We are always in limbo.